Challenges and Remedies for Diversifying Higher Education

Claude Steele on building trust, showing up and creating ‘beloved communities’

How can we build successfully diverse universities in which people feel they can contribute from the standpoint of their backgrounds and identities, and yet not be discriminated against on the basis of those backgrounds and identities?

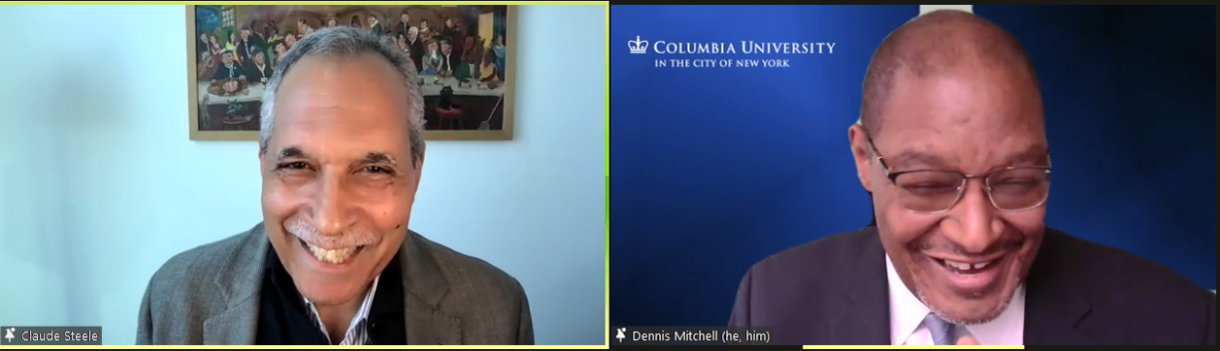

Claude Steele, professor of psychology at Stanford University, shared early insights from his forthcoming book in a talk he called “Churn: Life in the Increasingly Diverse World of Higher Education and How to Make It Work,” hosted by the Ivy+ Faculty Advancement Network.

The author of “Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do,” Steele is renowned for his research on stereotype threat and its application to the academic performance of underrepresented students.

In the virtual event on February 4, Steele argued that the basic question central the work of university faculty, staff and administrators is: “How do you have a successfully diverse community?” Steele described “successfully” diverse in terms of a community “in which people feel like they can contribute from the standpoint of their backgrounds and identities, but not be discriminated against on the basis on those backgrounds and identities.”

“I am working toward a set of remedies that I feel hopeful about,” Steele told the nearly 200 faculty leaders and senior diversity officers who attended the event. “I think there’s light at the end of the tunnel.”

Here are brief excerpts from Steele’s remarks, after which he joined participants for feedback and small group discussions.

‘Colorblindness’ and Contingencies of Identity

Looking to the mid-1960s, Steele described colorblindness as an offer on the table:

“The enfranchised member of society promised not to see race or gender, and instead to respond to people as individuals; on the side of the disenfranchised, the job was to assimilate to this society as fast as they can.”

“There are many good things to be said about this paradigm,” said Steele, listing policing, access to healthcare and access to investment capital as areas where colorblindness is a good thing. However, “colorblindness has blinded us to the significance of identity in people’s lives,” and, Steele went on, our institutions have not accommodated that significance. “We have used identity to organize and stratify this society, since the Old World met the New World … and we still have a considerable legacy from that system of organization.”

Capturing that legacy, Steele proposed, was the life of George Floyd:

“We are aware of his tragic ending, but we’re not as appreciative of the conditions of his life he has had to live all of his life that came to him because of his identity, of being a low-income African American. It’s like walking a gauntlet of disadvantages. He is born into a segregated community; lower-income; higher unemployment rates; less stable income. Families are going to be less able to endure economic shocks. There is less time given the instability of all that pressure to work with a young George Floyd and prepare him for school, and when he gets to school there will be fewer resources, fewer trained teachers, a harsher disciplinary system. If he gets into trouble, you know what kind of trouble he’s going to have with the criminal justice system. His family is going to have less access to good healthcare and less access to good food, all the way along.”

Steele uses a single term to label “all kinds of things” like those tied to Floyd’s identity as a low-income African American person: “contingencies of identity.” Given Floyd’s identity and the history of society, “those are the conditions of life that he has to deal with,” Steele said. “If we don’t really appreciate them as institutions of higher education and try to address them, to meet him where he is … we are not going to have a successfully integrated society.”

In continuing, Steele briefly recapped his foundational research on stereotype threat as a social-psychological contingency of identity. “If the situation that you’re in is important to you, schooling, for example, or the workplace, the prospect of being seen in terms of that negative stereotype can be upsetting and distracting, and can interfere with your functioning.”

Churn and the Tension Between Remembering and Forgetting

Steele proceeded to his new argument for his forthcoming title: when two people, or groups of people, each with their contingencies of identity, are attempting to communicate across differences, there is a lot going on cognitively, affectively and emotionally in these situations.

“Here we have an American conversation … these pressures are coming from our history, the roles our history has assigned us and the stereotypes that history has created to justify the roles that it has assigned us. We can think of things from a strictly colorblind frame of mind, that history is in the past … but as Faulkner famously said, the past is never dead, it’s not even past. We can feel this in a moment-to-moment way when we are interacting with each other. That history and its stereotypes and the pressures and tensions it creates can make it very difficult for us to trust each other.”

Without prior work done to build trust, Steele observed,

“…we’re left with these pressures to contend with in our efforts to relate to each other, to be part of a successfully diverse community in an institution or in a classroom. These kinds of pressures can enter the picture … a sort of tension between remembering and forgetting. ‘Do I remember how my group is seen and treated in society … and use that to interpret what’s happening to me in this immediate situation? Or do I just forget that, and trust the situation?’ That kind of tension is what I mean with the term churn.”

Churn is the worry about how one’s identity, in light of all of this context, plays out in the subjective experience of a diverse situation. To Steele, this “identity churn” is a “huge part” of the challenge of diversity, and trust is the critical issue in the functioning of our institutions.

Wiseness

How does one build trust, and reduce churn, through one’s own behavior? Steele invoked the concept of “wiseness.”

“It comes from a term that gays in the 1950s used to describe people who saw their full humanity, despite the stigmatization that that identity was under during that period of time. They referred to people who ‘got it’ as wise, as in, ‘No, he’s cool man, he gets us, he’s wise…’ The argument is that we have to develop that capacity to be wise in that sense … We have to develop the ability to see equal value and equal humanity in human difference.”

Individuals and institutions need that capacity to be wise, Steele argued, to have a successfully diverse community. He went on to discuss several studies (to be cited in his forthcoming book), often cleverly designed, that demonstrate the effectiveness of “wise” feedback. These studies interrogate the experiences of distrust and tension in the interactions of people of different identities and backgrounds. Such experiments show us the promise of how individuals can help others “forget” and “not stay in churn,” and also to manage their own churn.

From one “ingenious” study he admires, Steele discovered an effective remedy.

“When you’re in the face of difference and you want to be wise — that is, you want to see humanity in difference — the best thing to remind yourself of is that this is a learning opportunity. Have a learning mindset, a growth mindset. Think of yourself as a growth project: ‘I’m trying to learn how to function, and this is an opportunity to do that.’ Think of this as a learning opportunity.”

Physical Settings, Support to Meet High Standards, and ‘Toxic Ambiguity’

Another remedy Steele cited was in the settings that can either aggravate or alleviate churn. The physical context, the relative representation of identities in videos, any such cues in our environment, can produce a negative physiological response for the minoritized person in that situation. Fortunately, these negative cues — like a wall of photos of male faculty in a department with no women — can be easily fixed.

Among other studies cited by Steele, he described Rudy Mendoza-Denton’s survey finding that in one university’s physical science graduate programs, the women and minorities were not making the same progress toward publication as white students — except in the College of Chemistry.

“What is that unit doing that has made it easier for women and minorities to join into the culture and become as productive as the men in that culture? And what you see is inspiringly straightforward. They bring these graduate students in before they begin school, three weeks early … They try to bring them up to speed with regard to the cultural capital critical to succeeding in graduate school. ‘This is not about course grades, this is about getting involved in research,’ they tell them. ‘We’re going to have you talk to five faculty. They’re going to give you research project opportunities, and we want you to pick one. So that you know the appropriate rate of progress in this program, we would like the proposal by November 11, we would like the research done by March 3, and we’d like the paper submitted for publication by June 2’ — I’m making up these dates. ‘The faculty will meet with you every week, and that faculty will meet with a department-wide committee that helps advise faculty on mentoring.’”

One of the critical reasons Steele believes this college’s approach works to improve the diversity experience of this program is that it reduces what he called the “toxic ambiguity that can exist in many of our more laissez faire-structured” graduate programs.

“A lot of our graduate programs are more on the ‘talent will rise’ paradigm that allows a lot of informal networking systems to take over, and women and minorities often feel excluded from them. They often don’t know where they stand. They don’t know what the appropriate rate of progress is, they don’t know which is the best role model to look to. There's a lot of ambiguity, and into that ambiguity steps these toxic stereotypes and the worry about stereotypes. It inflicts on them a dysfunctional level of churn.”

The graduate program in chemistry, Steele proposed, is a “good example of a straightforward way of addressing churn, and perhaps a new standard for how our programs should exist.”

A Beloved Community and Who Shows Up

Steele turned to the heart of his belief about diversity’s value — and valuation — in higher education.

“One of the big problems with maybe our society in general but certainly our institutions, is that a value for diversity is not internalized as a central, personal, moral accountability. [Rather,] our central moral accountability is how good a scientist we are, how good a teacher we are. These things are central. How good we are with regard to diversity doesn’t have that kind of internal status and role in regulating us as self-accountability.

“We need to attend to that kind of internalization. There are examples throughout our history, and one big term that includes them is the idea of a ‘beloved community.’ These are the communities from which the early civil rights organizations were formed. It gives us a way to have an institutional approach. Our communities, our institutions need to aspire to that sort of esprit of a beloved community.”

As the session’s end, Steele concluded with thoughts for an audience seeking optimism in the face of our persistent challenge.

“The reason I’m hopeful is that trust-building and reducing churn is a game played on the ground. Everybody can play this. You don’t have to have the same identity as your students and your colleagues. You don’t have to be matched up in that way, you don’t have to have an especially sophisticated cultural grasp of everything — these things would be helpful, I don’t want to put them down — but trust building is a more fundamental game played on the ground. It’s who shows up. It’s who listens with a focus on learning. It’s who offers real, concrete, clear, supported, collaborative help going forward. Those things build trust and enable successfully diverse communities.”